The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) Inquiry concluded over a year ago by asserting that the ongoing systemic neglect and legacy of colonial violence imposed upon Indigenous women and girls constitutes genocide. Despite this, a year later, Indigenous women and girls continue to be violated and marginalized at rates much higher than those in the general population.

For nearly 50 years, Dixon Transition Society’s main focus has been to eliminate violence against women and children. However, over the past few years, inspired by the hearings and findings of the MMIWG Inquiry, we have come to understand that this group of Canadians has been tragically underserved and under-protected. While the Inquiry calls on the Federal, Provincial and Indigenous Governments as well as the RCMP to implement changes based on the 200 recommendations, and Dixon has pivoted its perspective and begun offering culturally sensitive services that are relevant to Indigenous women, all Canadians have responsibilities to make this better.

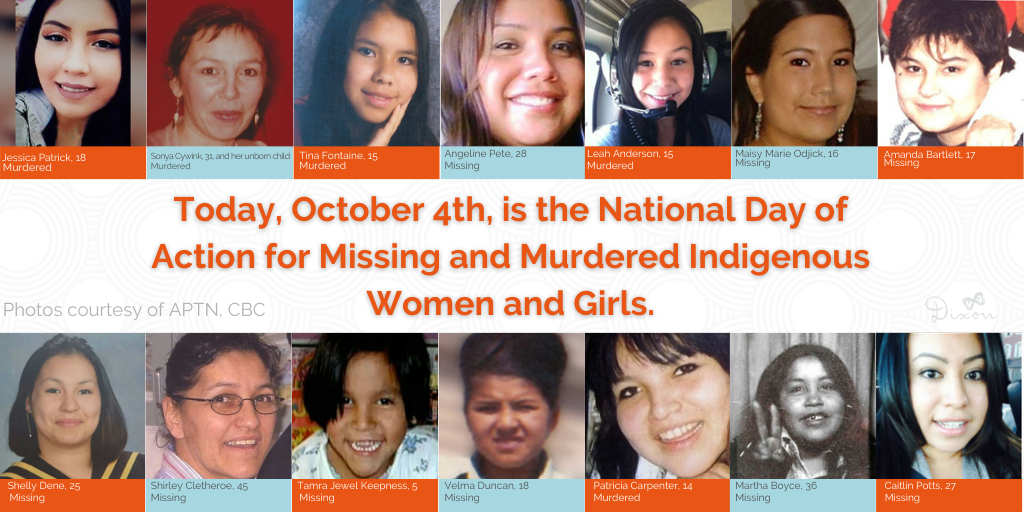

So today, October 4th, as we observe the National Day of Action for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, we add our voice to the collective call to bring an end to the injustices suffered by Canada’s Indigenous Women and Girls. As Canadians, let’s make a change. Let’s look at this issue through an empathetic lens. Let’s create some space for understanding of the causes of the systemic abuses that our fellow Canadians continue to experiences. And let’s begin by acknowledging that everyone should be entitled to lives free from violence.

Join us as we take a look into just how pervasive violence against Indigenous women and girls is, and some of the reasons behind it.

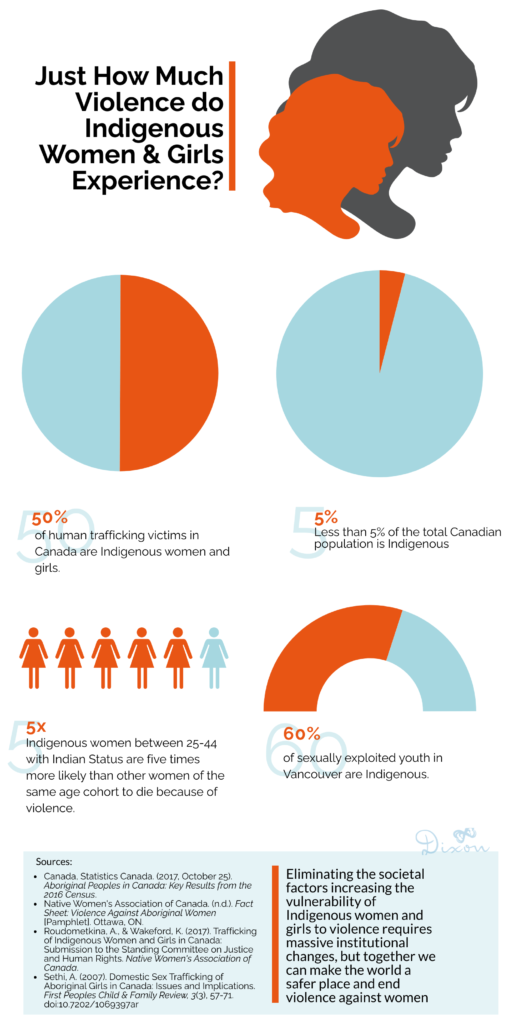

Just how much violence do Indigenous women and girls experience?

Ascertaining the exact number of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls is difficult: RCMP data suggests figures of around 1200, whereas the databases kept by Indigenous women’s groups suggest the number could be over 4000.

Most of what we study comes from official crime data, which has not included information about race until this year. Further, not every case of violence is reported to police or non-profit organizations. Survivors may choose not to report for a wide range of reasons, and the unfortunate reality is that many women and girls do not live to tell their story.

What we do know from the information we have, however, is clear: Indigenous women and girls experience violence much more frequently and much more severely than non-Indigenous women and girls.

Statistically speaking, we know that:

- Indigenous women and girls represent 24% of female homicide victims,1 despite the fact that Indigenous people account for less than 5% of the overall population.2

- The rate at which Indigenous women and girls are killed has continued to increase whereas the rate at which non-Indigenous women and girls has declined over time. 1

- The rate at which Indigenous women report experiencing sexual assault is more than 3x higher than non-Indigenous women.3

- Indigenous women report experiencing recent spousal violence at a rate of twice that of non-Indigenous women (15% vs 6%).4

- Indigenous women are more likely to be injured as a result of spousal violence (59% vs 41%).4

- 52% of Indigenous women who report violence are more likely to fear for their lives than 31% of non-Indigenous women. 4

- Indigenous women between 25-44 with Indian Status (yes, it’s still called that) are five times more likely than other women of the same age cohort to die because of violence.5

- The murder cases of Indigenous women might be less likely to be solved than those involving non-Indigenous women. Only 53% of the murder cases in the Native Women’s Association of Canada’s Sisters In Spirit database have been solved, compared to 84% of murder cases across Canada.5

- Indigenous women are almost three times more likely to be killed by a stranger than non-Indigenous women.5

- According to RCMP data, 94% of human trafficking cases involve victims trafficked from places within Canada, with Indigenous women being overrepresented among the victims. Further studies suggest that roughly 50% of human trafficking victims are Indigenous women and girls.6

- 60% of sexually exploited youth in Vancouver are Indigenous.7

Why do Indigenous women and girls experience such disproportionately high rates of violence?

While each individual woman and girl has her own unique set of exposures to violence, studies by academic institutions, government agencies and non-governmental organizations have consistently identified several systemic factors placing Indigenous women and girls at risk.

Studies suggest that after factors like educational attainment and employment are controlled for, Indigenous people are roughly three times more likely to be victims of violent crimes than non-Indigenous people.8 Several studies, including the MMIWG Inquiry, have concluded that one way racism against Indigenous women and girls often manifests is through the over-sexualization of their bodies. Indigenous women and girls are often portrayed and perceived as inherently sexually available, leading to a cultural evaluation of violence against them as “lesser.”9 Because of cultural values we have surrounding sexuality, this also predisposes Indigenous women and girls to being perceived as inherently more “inferior,” “deviant,” and “dysfunctional,” even though this isn’t true.9

These racist ideas about Indigenous women and girls may explain why trafficking and sexual exploitation of them is often portrayed as a problem of consensual sex work rather than abuse in both policy and media. It may also explain why issues concerning Indigenous girls are often absorbed into the umbrella of “Indigenous women’s issues.”

Indigenous peoples have been socioeconomically marginalized due to systemic oppression

Among Indigenous peoples specifically, the unemployment rate is more than double that of non-Indigenous peoples in Canada10, and a lack of culturally-sensitive, low-barrier services leaves Indigenous women with fewer resources should they choose to flee from violence.

Furthermore, poverty amongst Indigenous people can force Indigenous women and girls into precarious situations. Indigenous peoples make 33% less money per year on average than non-Indigenous people.10 Further, 84% of on-reserve households do not have enough income to cover the cost of adequate housing.7 Without other options, many women are forced to resort to means of subsistence, such as participating in street-level sex work or moving to an unfamiliar city without many resources or supports, to make ends meet.

Colonialization & the residential school system have created intergenerational trauma

For many Indigenous women and girls, abuse is normalized as they grow up, making it harder for them to recognize their relationships as such.11 Scholars have argued that the violence in Indigenous families and communities “is almost always linked to individual or collective trauma and the need for healing” resulting from colonization and the impact of residential schools.12 Within the residential school system, laws mandated that children were forcibly removed from their communities and taken to boarding schools away from their communities. Sexual, physical, and mental abuse were rife at these schools,13 with children being deliberately and systemically starved at some.14 The effects this abuse had on individual lives had is immeasurable, and the thorough and systemic nature of it effectively ensured it would continue through the generations. After all, where do you learn how to cope with your trauma in a productive manner and become a healthy parent when everyone around you is still learning how to deal with their own abuse?

So where do we go from here?

Despite the atrocities committed against them, Indigenous peoples have always shown incredible tenacity and resilience in their resistance. At every stage of Canada’s colonization, they have advocated and fought for their rights.

Eliminating the societal factors increasing the vulnerability of Indigenous women and girls to violence requires massive institutional changes. The MMIWG inquiry has outlined several directives for all Canadians to redress the MMIWG genocide. These directives focus on principles of decolonization, inclusion, cultural competency, trauma-informed approaches and Indigenous sovereignty. These are principles we can all follow in our daily lives.

As settlers, the first thing we can do is learn to listen to Indigenous peoples. We can learn so much about the crisis and how to help by listening to their stories with open ears. The best way to become good allies to Indigenous peoples is to learn how from Indigenous peoples. Settlers also need to take a more active stance by challenging racism in our lives and pressuring our government to do the same. When you hear something racist or sexist, point it out. There is a lot of work to be done, but if we all work together, we can put an end to the MMIWG genocide once and for all.

If you or someone you know would like some help leaving a violent situation, please do not hesitate to reach out. At Dixon, you can call our 24-hour intake line at 604-298-3454. For resources outside of Burnaby, please call VictimLink BC at 1-800-563-0808. If you are in immediate danger, please call 911.

If you require immediate emotional assistance with matters concerning MMIWG, please call 1-844-413-6649.

If you have any information on the cases of any of the women or girls featured in the heading of this blog, please contact authorities or [email protected].