At Dixon, we know that the care we provide is healthcare. Many of the women and children walking through Dixon’s doors are accompanied by the lasting effects of trauma.

The health consequences of experiencing domestic violence can be particularly severe and long-lasting. However, with swift, specialized treatment, these effects can be mitigated. Still, we don’t often think of domestic violence as a complex and serious health risk indicator in our everyday conversations.

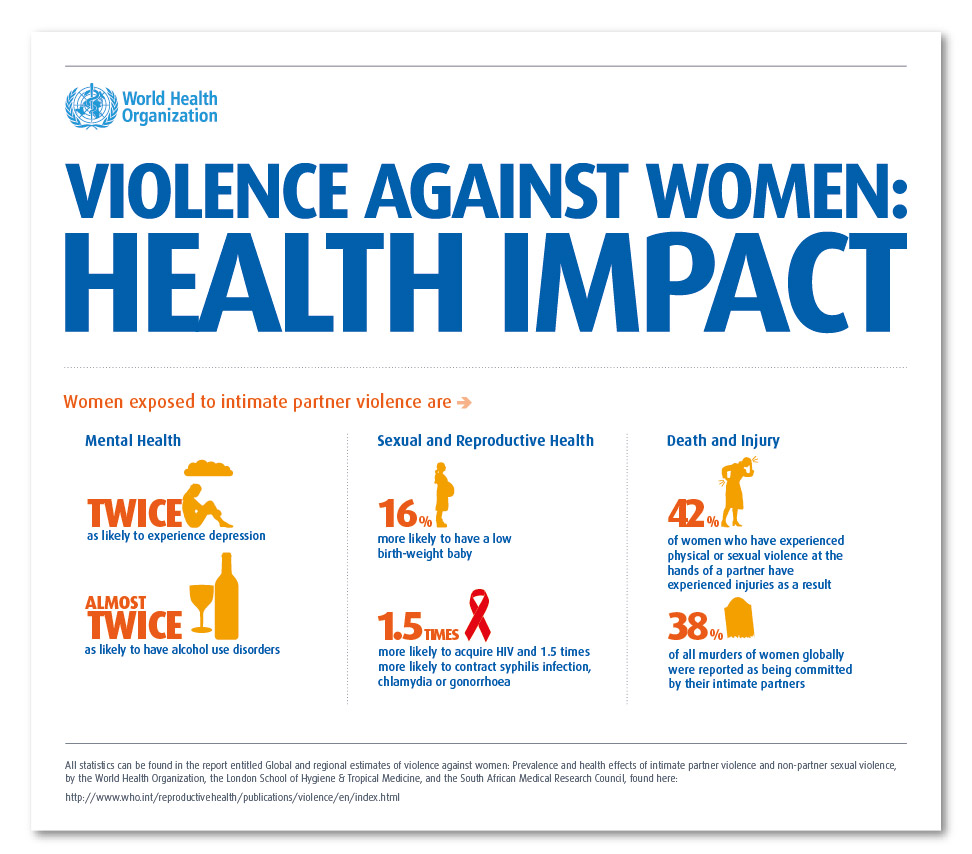

According to the World Health Organization, surviving domestic violence can have negative health effects on a woman and her children, encompassing many different aspects of health, including physical health, sexual and reproductive health, and mental health.

Even with everything we know about the health effects of domestic violence, treatment can be difficult. To learn why, we sat down with Peggy, Dixon’s Clinical Supervisor.

Learning to process and cope with trauma often requires intensive care

When we’re talking about the health of domestic violence survivors, says Peggy, it’s important to keep in mind that the cases of these individuals are incredibly complex.

People can develop post-traumatic stress responses when exposed to trauma. Post-traumatic stress responses are essentially our body’s way of protecting us from environmental threats, both physically and mentally. These responses help prepare our bodies to adapt to the challenges we might face. Unfortunately, they can become maladaptive. Chronic stress is connected to every major health concern.

Peggy also tells us that the duration and magnitude of these responses can vary according to our own personal resiliency. Post-traumatic stress responses can develop into post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD itself is a complicated disorder to diagnose. Learning to cope with triggers associated with one’s PTSR/PTSD often requires time and help. This learning process can be very difficult and may last an entire lifetime.

Concurrent disorders can further complicate a situation. For example, in trying to cope with post-traumatic stress, some individuals might develop addictions. This makes their cases even more complex. Both of these conditions often require specialized care, which many might find difficult to access.

The needs of children often go unmet

Peggy stressed that children need to receive specialized treatment as well (which is why our Child Support program is so vital). When it comes to addressing domestic abuse, children are often treated as a sort of add-on to their mother’s case. Children also experience trauma living in the same toxic environments as their mothers. Many children also experience stressors like poverty, racism, or the challenges associated with immigration.

The focus of interventions surrounding children often centers around housing, childcare, and schooling. Specialized psychological care is often left out of the equation. As a result, caregivers may be tasked with helping children manage complex traumatic stress responses. In many cases, these protective responses are mislabeled as “behavioural problems.”

Like adults, kids can experience complexly interwoven health conditions. Sadly, the treatments for these conditions tailored towards children aren’t always readily accessible. As a result, it is often difficult for children to get the help they need.

The root causes of survivors’ health problems are often social

Domestic violence isn’t a purely psychological and physical ailment, but a social one. Exposure to domestic violence is a social determinant of health. Social determinants of health are the various economic, environmental, and social elements and systems shaping an individual’s daily life. These systems often shape situations of domestic violence, as well.

For example, we know that domestic violence is more prevalent in rural than urban areas. This is because of a variety of factors, ranging from entrenched gender inequities to a lack of mental health and social services. These factors shape a woman and her children’s experiences of domestic violence. In turn, these factors then affect their health.

Poverty, Peggy notes, is another major social determinant of health. It is strongly linked to domestic violence, in many cases increasing the likelihood of experiencing violence. Poverty is also a source of considerable stress in and of itself and is perfectly capable of creating complex health issues on its own.

Unfortunately, poverty is a condition that tends to follow women and their children when leaving a violent situation. Many women fleeing domestic violence are single mothers or become them. Single mothers tend to fall into the “low bracket” of the social safety net and tend to lie on the margins of our collective awareness. Because of this, finding support can be difficult.

Organizations caring for women and children fleeing violence are not treated like healthcare organizations

According to Peggy, adopting a feminist, political analysis of the non-profit sector reveals that Canadian non-profits tend to end up servicing the most complex health conditions with the fewest resources. Many women and children fleeing violence face multiple challenges due to systemic oppression.

For example, any women fleeing domestic violence are single mothers. Single mothers tend to fall into the “low bracket” of the social safety net and tend to lie on the margins of our collective awareness. Because of this, finding support can be difficult.

When trying to access care, women may face many barriers. Racism entrenched in the healthcare system can lead staff to provide BIPOC with poorer care. Some women may even be altogether excluded from accessing care due to their immigration status. As a result, low-barrier, anti-oppression organizations like Dixon can be critical in helping a woman and her children heal.

Part of the problem is that there is a competition among non-profits for funding. Unlike hospitals and clinics, non-profits often need to apply for grant funding to support their operations. Consequently, the care provided by non-profits is not afforded the same level of funding as the care provided by the healthcare sector. Sadly, this includes transitional housing societies like Dixon.

This lack of resources can be stressful for staff. It can also lead to a lack of engagement among them. The population living in transitional housing is highly complex and marginalized. As a result, any lack of engagement and consistency might be detrimental to clients’ healing.

So how can we effectively treat women and children who are fleeing domestic violence?

According to Peggy, experiencing domestic violence requires holistic, trauma-informed care at both clinical and organizational levels. Trauma-informed approaches recognize that in order to provide effective care, care teams need to have a complete picture of a client’s lived experiences.

Because of this, trauma-informed care entails a paradigm shift. This kind of care doesn’t aim to pathologize an individual’s experiences, but instead focus on holistic healing. Trauma-informed care necessitates that professional resources enter into the low-barrier spaces that marginalized people can readily access.

In a trauma-informed approach, service providers tailor their care to the client. For example, when working with a child, clinical art and play therapy could be enlisted.

Trauma-informed approaches involve principles of empowerment, collaboration, and transparency. This care requires that staff are cognizant of the power imbalances implicit in the provider-client relationship. In a trauma-informed setting, staff work with clients to make decisions on how to move forward, not for them. This approach can improve health outcomes by offering clients them the chance to engage more fully in their care and develop a more trusting relationship with their support teams.

Additionally, trauma-informed approaches also help keep staff healthy and avoid burnout. Avoiding burnout allows staff to continue to be reliable supports.

At Dixon, we know that the care we provide is healthcare

We incorporate a feminist, trauma-informed approach into the care we provide. We recognize that in recovering from an experience with domestic violence, women and children need to be able to reclaim their sense of control over their own lives. Our woman-centred approach recognizes that each woman that steps through our doors knows the needs of her and her family better than anyone else. This recognition enables us to provide support and specialized care while respecting the autonomy of our clients.

To our knowledge, Dixon is the only transitional house in British Columbia with a clinical consultant supporting staff. At Dixon, we know that caring for our staff has a ripple effect. In caring for our staff’s wellbeing, we can ensure that the families at Dixon have consistently reliable supports to turn to.

Our comprehensive healing plan helps guide the care of the women and children we serve. Families at Dixon have access to mindfulness programs and counselling. Dixon’s continuum of care incorporates both restorative and resiliency practices. Dedicated Women Support Workers and Child Support Workers are on-site to support families as they create and pursue their goals.

If you or someone you know would like some help leaving a violent situation, please do not hesitate to reach out. At Dixon, you can call our 24-hour intake line at 6044-298-3454 or get in touch by email. For resources outside of Burnaby, please call VictimLink BC at 1-800-563-0808. If you are in immediate danger, please call 911.